I woke up on top of the picnic table where Marty had laid me out like a corpse. I looked straight up into an endless azure uninterrupted by clouds or sun, and for a few moments I just gazed and enjoyed the freedom from focusing, the sight of nothingness. I could smell algae from the lake water in my hair and on my clothes and that drew my vision down to the objects around me. The sun was warming the sky, and Marty had stoked the fire and brought some flames back to help chase the autumn chill away. As my senses began to return, I recognized that I was freezing and that my throat was raw from the pot and the lake water and sleeping out like that. Marty, however, looked cool and was drinking coffee that he somehow knew how to make over an open fire. I remember thinking as I lay there looking like a bum on a park bench, that the remarkable thing about Marty was that he never seemed scruffy or slovenly. It could be five in the morning and he could have been up all night chain-smoking cigarettes and drinking beer, and yet he could remain as articulate and balanced, as cool and smooth, as if he’d just stepped out of a shower and was ready to go for the day. Even his disheveled appearance seemed somehow always right and almost intended. He was as natural as the sky or the flames in the fire. Life and Marty were blended to such an extent that living, experiencing, was all Marty was. I envied that about him. To be in life was what I desired, instead, lying there on top of that picnic table, I felt the first pangs of my lot.

Marty walked over to me and held out a tin cup of black coffee. I sat up, hung my legs off the end of the table, and carefully took the cup. I sipped the coffee and worked some of the sleep out of my head. On top of the picnic table, Marty sat down beside me. He lit a cigarette and looked at me. I felt ashamed sitting there beside him like that after what had happened the night before. I almost felt like I should thank Marty or something for pulling me out of the water. But instead of gratitude, the fact that I felt obliged to Marty irked me. I had wanted to prove Marty’s equal, his peer, instead I proved to be nothing but a struggling kid. The feelings of obligatory appreciation and of disappointment coupled with sleeping in wet clothes in the cold air urged me away from Marty at that moment. Marty had control, he was directing the script, and it occurred to me that as long as I was with Marty, it would be this way. Marty needed it thus. I stood up, set my cup on the table, retrieved my bag from the car, and started the long walk to the regular camp sites where there was a shower house.

It felt good to get away from Marty then, to regroup under a hot shower. I had no idea what time it was, but the shower house was empty. I could tell by the musky stale air that others had already been and gone. A bar of soap had been left in the shower stall by some camper, and I used it. I lathered my body and face while standing with my back to the water. I wanted to be covered in the suds before rinsing them off. I have always done this, I don’t know why, but there is something I like about being under the soap lather, the cleanness of it all. When I left the shower house I felt better. The sun was out in full and the dry air was quickly warming up. I still wasn’t ready to face Marty though, so I walked around the regular camp grounds for a bit. There were not many campers there at that time of year, and the few who were set up were mostly senior citizens on permanent lots, or guys in tents who had risen much earlier and were already out on their fishing boats. A few people still sat around morning campfires sipping coffee or reading papers that they had bought at the ranger station. The only people from that morning walk that I can remember in detail are a group who were camping in tents around a trailer. There were ten or twelve people in all, including the children, and I remember thinking that they looked happy. The couple, who I imagined to be the grandparents, seemed to own the trailer, and the tents seemed to belong to the grown children and their children. I have no basis for these assumptions, perhaps the people were not even related, but all in some kind of church group or something; yet, I like to think they were a big family. Scattered throughout the treed site were coolers and vinyl clothing bags and cooking equipment. There were four bikes, all laying on their sides, haphazardly dropped wherever the last rider’s attention shifted to something else. Between two trees, a clothesline hung and towels and shirts and shorts and rags of all sizes were pinned to it. I carried my dingy cloths under my arm in a ball, their dampness soaking into the side of my t-shirt. For a moment I thought maybe I could just walk over and hang my stuff on their line and sit down around their fire and just slip into their history, like I had always been there, like I was part of them. They all stopped talking for a moment as they noticed me no longer walking but just standing there in front of their site, just standing there with wet stringy hair and dirty laundry under my arm, and they looked at me with wonderment. I didn’t say anything, I just stood there and peered in for another moment, then I lowered my eyes, turned, and walked back to the wilderness sites.

Saturday, July 23, 2011

Friday, July 22, 2011

A Wilderness Site: Part IV

Eventually the fire burned down to mostly the hot red glow of coals and the meteor shower subsided, and I decided to go find Marty. I wasn’t sure exactly where on the shore he would be, but I figured since the park was mostly empty that I’d probably see his lantern. I carried a small flashlight to light the trail from the site to the shore, but once I made it out of the woods, the waxing moon, which was now lighting the sky and reflecting off the water, made seeing relatively easy. The lake was calm and glassy and along the shore I could see five or six lantern lights spaced intermittently. The closest one was Marty’s, and I approached it without difficulty.

Marty hadn’t caught any fish worth keeping, yet he seemed uninterested in returning to the camp. He said that he too had seen the meteors, but that he was glad they were over. He said that they were bad for fishing, that the streaking lights had strange effects on the fish and kept them away from the surface. He said now that the moon was full, the fish would stay down even lower. Fishermen always seem to know weird stuff like that. After several more casts, Marty put his rod down and lay back on the big rock on which he was sitting. He had a couple cans of beer soaking in the water to make them cold, and he told me to reach in and grab two. I did and Marty sat back up and took one. I opened the other can and took a sip. “I got some pot if you want some.” I had been carrying it with me for several days with the hope of impressing Marty. I really never smoked much pot, but I knew Marty did, and so I figured he would be impressed that I had some for us. But as soon the words left my mouth, I knew it wasn’t the way I had wanted to tell him. I had wanted to be smooth about it, like pull a joint out of my pocket and hit him with some awesome line, but instead, I sounded like a kid, and he smirked. He set down his beer and reached his hand toward me. I pulled the plastic bag out of my pocket and handed it to him. He held it close to the lantern, opened the bag and sniffed it. Then he smirked again. “Hell, this is Mexican shit. I hope you didn’t give noth’n’ but pesos for it. It ain’t even all pot.” He reached into his tackle box and lifted out a bag. “Now look at this. This stuff’s for real.” He grinned and opened his bag. Fast and skillfully, he rolled a joint. I wanted to ask him to show me how he did it, but I was already embarrassed, and I figured I’d better wait a bit before asking a question like that.

He was right though, about my pot being weak, because when I took a few hits of his joint, everything started spinning, and I wasn’t exactly sure where I was, I mean I was not used to being around Marty, and the camp was new to me too. Still, I knew I was really high, and I knew I didn’t want Marty to think I couldn’t handle it, so I focused all my concentration on thinking about the fire and the stars and the meteors, but the more I focused my attention, the more I forgot to focus my attention: the more I tried not to be disoriented, the more disoriented I became. And the cycle spiraled down with the pot holding me tight, and I began to imagine that I could not breath, that a clamp was around my chest and that with my every breath, it tightened, and that all I could do was suck in tiny amounts of air and pant. I even forgot about looking cool and started a paranoid struggle for survival. I must have hyperventilated at that point because my panting became so bad that I eventually couldn’t breath at all, and Marty had to cup his hands around my mouth and talk me down. I don’t know how long that lasted, but eventually I blacked out, and the next thing I knew, Marty was standing knee-deep in the water pulling me to the shore, and I was coughing and all mixed-up. I think Marty probably threw me in the water to revive me, but I never had a chance to ask him.

Marty hadn’t caught any fish worth keeping, yet he seemed uninterested in returning to the camp. He said that he too had seen the meteors, but that he was glad they were over. He said that they were bad for fishing, that the streaking lights had strange effects on the fish and kept them away from the surface. He said now that the moon was full, the fish would stay down even lower. Fishermen always seem to know weird stuff like that. After several more casts, Marty put his rod down and lay back on the big rock on which he was sitting. He had a couple cans of beer soaking in the water to make them cold, and he told me to reach in and grab two. I did and Marty sat back up and took one. I opened the other can and took a sip. “I got some pot if you want some.” I had been carrying it with me for several days with the hope of impressing Marty. I really never smoked much pot, but I knew Marty did, and so I figured he would be impressed that I had some for us. But as soon the words left my mouth, I knew it wasn’t the way I had wanted to tell him. I had wanted to be smooth about it, like pull a joint out of my pocket and hit him with some awesome line, but instead, I sounded like a kid, and he smirked. He set down his beer and reached his hand toward me. I pulled the plastic bag out of my pocket and handed it to him. He held it close to the lantern, opened the bag and sniffed it. Then he smirked again. “Hell, this is Mexican shit. I hope you didn’t give noth’n’ but pesos for it. It ain’t even all pot.” He reached into his tackle box and lifted out a bag. “Now look at this. This stuff’s for real.” He grinned and opened his bag. Fast and skillfully, he rolled a joint. I wanted to ask him to show me how he did it, but I was already embarrassed, and I figured I’d better wait a bit before asking a question like that.

He was right though, about my pot being weak, because when I took a few hits of his joint, everything started spinning, and I wasn’t exactly sure where I was, I mean I was not used to being around Marty, and the camp was new to me too. Still, I knew I was really high, and I knew I didn’t want Marty to think I couldn’t handle it, so I focused all my concentration on thinking about the fire and the stars and the meteors, but the more I focused my attention, the more I forgot to focus my attention: the more I tried not to be disoriented, the more disoriented I became. And the cycle spiraled down with the pot holding me tight, and I began to imagine that I could not breath, that a clamp was around my chest and that with my every breath, it tightened, and that all I could do was suck in tiny amounts of air and pant. I even forgot about looking cool and started a paranoid struggle for survival. I must have hyperventilated at that point because my panting became so bad that I eventually couldn’t breath at all, and Marty had to cup his hands around my mouth and talk me down. I don’t know how long that lasted, but eventually I blacked out, and the next thing I knew, Marty was standing knee-deep in the water pulling me to the shore, and I was coughing and all mixed-up. I think Marty probably threw me in the water to revive me, but I never had a chance to ask him.

Thursday, July 21, 2011

A Wilderness Site: Part III

We had borrowed a two-person tent from Aunt Janice, and while Marty set that up, I rummaged through the single bag of food we had brought with us. Marty drew his hunting knife from a leather scabbard hooked to his belt, cut open the bag of ice, and dumped it in the cooler over the cans of beer. I remember thinking that Marty loved to use that knife. He always wore it on his belt. It had a six-inch blade which was hooked on the end and a row of jagged saw teeth on the top side. The blade was flat black and the handle was oak with ivory inlays and grooves for easy handling. When unfolded and locked into position, the knife simply looked dangerous. I had no idea what a person would do with the hook and saw features, but Marty was adept at handling the tool and used it whenever he could.

I ate a powdered donut and then went looking for some kindling with which to start a fire while Marty finished arranging everything. When I got back to the site with an armload of twigs and small branches, Marty and his fishing gear were gone. On the face of the hatchet, Marty had left some stick matches with which to start the fire. The day was growing dark and cooling off, and I arranged the kindling over some newspaper and lit the paper with one of the matches. We had stopped outside the park and picked up a bundle of firewood from someone who had had it stacked in parcels in his front yard beside a little box in which to deposit money. I remember thinking about that box of money sitting there unattended and wondering why no one took it. I would have taken it myself, but something about the set-up prevented me from doing it, almost like instead of just stealing a few dollars from an unattended till, taking this money would be dishonorable, almost shameful. If the honor is in the hunt, this system, by eliminating the hunt, eliminated the honor. It even created the opposite effect. Instead of stealing the money, it felt good to do the right thing and pay for the bundle. I remember liking the fact that whoever had stacked that wood was trusting me.

It was good dry wood we had purchased, and I started a decent fire without much trouble. To build a fire like that felt good, like I was a pioneer living off the land or something. The flames warmed the air around the fire, and the heat brushed against the skin of my face. I sat on the ground and looked at the fire for a long time. The orange and red flames danced around the crackling wood and every so often a small ember would shoot out of the rusty metal ring like the last act of an old circus performer, its red tail quickly evaporating behind its arced path, its intensity quickly fading into darkness. I sat there and watched that fire for a long time, and when I eventually looked up at the sky, I saw the millions of stars which only seem to shine way out away from the city, away from the houses, and like the embers which popped and arched out of the fire on that night, I watched a meteor shower with hundreds of streaking particles burning blue into the atmosphere.

The memory of that fire, those stars, and the meteors seems strangely magnetic to me now, and, on cool fall nights, I often long to go back to that site and light another fire and look at those same stars, and watch the particles of dust and rock incinerate as they try to break into our sky, but I know I will never go back. Perfect moments can not be fabricated––they just appear and then they are gone. The real trick is to recognize them when they are happening, and what I most regret is that back then, I hadn’t, and that now I long for that moment that has grown to become better than I knew it to be.

I ate a powdered donut and then went looking for some kindling with which to start a fire while Marty finished arranging everything. When I got back to the site with an armload of twigs and small branches, Marty and his fishing gear were gone. On the face of the hatchet, Marty had left some stick matches with which to start the fire. The day was growing dark and cooling off, and I arranged the kindling over some newspaper and lit the paper with one of the matches. We had stopped outside the park and picked up a bundle of firewood from someone who had had it stacked in parcels in his front yard beside a little box in which to deposit money. I remember thinking about that box of money sitting there unattended and wondering why no one took it. I would have taken it myself, but something about the set-up prevented me from doing it, almost like instead of just stealing a few dollars from an unattended till, taking this money would be dishonorable, almost shameful. If the honor is in the hunt, this system, by eliminating the hunt, eliminated the honor. It even created the opposite effect. Instead of stealing the money, it felt good to do the right thing and pay for the bundle. I remember liking the fact that whoever had stacked that wood was trusting me.

It was good dry wood we had purchased, and I started a decent fire without much trouble. To build a fire like that felt good, like I was a pioneer living off the land or something. The flames warmed the air around the fire, and the heat brushed against the skin of my face. I sat on the ground and looked at the fire for a long time. The orange and red flames danced around the crackling wood and every so often a small ember would shoot out of the rusty metal ring like the last act of an old circus performer, its red tail quickly evaporating behind its arced path, its intensity quickly fading into darkness. I sat there and watched that fire for a long time, and when I eventually looked up at the sky, I saw the millions of stars which only seem to shine way out away from the city, away from the houses, and like the embers which popped and arched out of the fire on that night, I watched a meteor shower with hundreds of streaking particles burning blue into the atmosphere.

The memory of that fire, those stars, and the meteors seems strangely magnetic to me now, and, on cool fall nights, I often long to go back to that site and light another fire and look at those same stars, and watch the particles of dust and rock incinerate as they try to break into our sky, but I know I will never go back. Perfect moments can not be fabricated––they just appear and then they are gone. The real trick is to recognize them when they are happening, and what I most regret is that back then, I hadn’t, and that now I long for that moment that has grown to become better than I knew it to be.

Wednesday, July 20, 2011

A Wilderness Site: Part II

It was twelve hours northwest to the lake, and the afternoon sun sat in our laps most of the way. Sitting behind sunglasses and the car’s visors, we really didn’t say much to each other as we sped across the northern landscape. The foliage beside the empty road where Marty pulled off to take a rest from driving was in full splendor––purple, maroon, orange, red, and yellow. The wind was blowing strong enough to keep the boughs gently rocking and the leaves mixing together like the tumbling hues in a kaleidoscope.

Whenever we stopped to get gas, I jumped out and checked the air in the tires so people would see us together––the cool kid with long hair and the disheveled guy with a tattoo of a whale on his arm. At the time I thought whoever saw us must have thought we were real serious men who knew the meaning of cool, who really had their stuff together. Yesterday I saw two guys at the gas station looking like a modern version of how I imagined Marty and I looked. One of them was leaning against the car waiting for the pump to finish while the other one, sitting in the front passenger seat, was rocking his head to the loud bass of their music. Something inside me wanted to go up to them and reassure them that everything was all right, but that would not have done any good, I know; besides, there was also something about looking at those guys that made me feel embarrassed, like looking at myself in a home movie.

Back in the car, in between cassette tapes of old rock songs, I asked some questions about Europe, but Marty was not interesting in telling stories. He just wanted to listen to the loud music, drink beer and drive. At the first gas station, he had picked up two twelve-packs of beer and was already on his third can before I even got through half of my first. Back then I pretended to like beer, but truthfully it tasted sour to me. I never told people that though, and usually I could drink as much as anyone I knew. But Marty had acquired the taste for beer and drank it like water. In the car, aside from the heavy drinking, Marty also smoked continuously. He went through cigarettes one right after another and would have never thought to vent the smoke out the window if I hadn’t had opened mine. He smoked American cigarettes and told me that European cigarettes tasted like crap and that Mexican cigarettes were made out of donkey dung. I remember thinking how cool it was to be in a car with someone who knew that, that I wanted desperately to know that too, that I urgently wanted to use that line on someone. That was about all he really said for the whole twelve hours. He would not let me drive, though.

When we arrived at the lake it was growing dark and what little warmth the autumn sun had provided that day was quickly changing into the cool dry air of a late fall night. The ranger station was closed already, and Marty self-registered us on a wilderness site. He took a bag of ice from the unlocked freezer beside the station, and we drove back to select a lot. There were no water spigots or electrical outlets on the wilderness sites, but Marty said nobody hassled you there so it was worth the trade-off. I was glad he had chosen a secluded site. The few times I had gone camping with Mom and Aunt Janice, it had always seemed bizarre to me to drive hundreds of miles from home to sleep in a tent twenty feet from other people who were doing the same thing you were, only usually with better equipment. Back then, we mostly tended to stake our tents next to big trailers and motor-homes and lie in our nylon shells listening to air-conditioners and watching the soft blue glow of portable televisions illuminating the trailer windows as we walked to the toilets. When we set up beside someone like that, with the whole outfit, I always felt like I was a refugee in someone’s back yard. At least the wilderness site moved us away from all that.

Whenever we stopped to get gas, I jumped out and checked the air in the tires so people would see us together––the cool kid with long hair and the disheveled guy with a tattoo of a whale on his arm. At the time I thought whoever saw us must have thought we were real serious men who knew the meaning of cool, who really had their stuff together. Yesterday I saw two guys at the gas station looking like a modern version of how I imagined Marty and I looked. One of them was leaning against the car waiting for the pump to finish while the other one, sitting in the front passenger seat, was rocking his head to the loud bass of their music. Something inside me wanted to go up to them and reassure them that everything was all right, but that would not have done any good, I know; besides, there was also something about looking at those guys that made me feel embarrassed, like looking at myself in a home movie.

Back in the car, in between cassette tapes of old rock songs, I asked some questions about Europe, but Marty was not interesting in telling stories. He just wanted to listen to the loud music, drink beer and drive. At the first gas station, he had picked up two twelve-packs of beer and was already on his third can before I even got through half of my first. Back then I pretended to like beer, but truthfully it tasted sour to me. I never told people that though, and usually I could drink as much as anyone I knew. But Marty had acquired the taste for beer and drank it like water. In the car, aside from the heavy drinking, Marty also smoked continuously. He went through cigarettes one right after another and would have never thought to vent the smoke out the window if I hadn’t had opened mine. He smoked American cigarettes and told me that European cigarettes tasted like crap and that Mexican cigarettes were made out of donkey dung. I remember thinking how cool it was to be in a car with someone who knew that, that I wanted desperately to know that too, that I urgently wanted to use that line on someone. That was about all he really said for the whole twelve hours. He would not let me drive, though.

When we arrived at the lake it was growing dark and what little warmth the autumn sun had provided that day was quickly changing into the cool dry air of a late fall night. The ranger station was closed already, and Marty self-registered us on a wilderness site. He took a bag of ice from the unlocked freezer beside the station, and we drove back to select a lot. There were no water spigots or electrical outlets on the wilderness sites, but Marty said nobody hassled you there so it was worth the trade-off. I was glad he had chosen a secluded site. The few times I had gone camping with Mom and Aunt Janice, it had always seemed bizarre to me to drive hundreds of miles from home to sleep in a tent twenty feet from other people who were doing the same thing you were, only usually with better equipment. Back then, we mostly tended to stake our tents next to big trailers and motor-homes and lie in our nylon shells listening to air-conditioners and watching the soft blue glow of portable televisions illuminating the trailer windows as we walked to the toilets. When we set up beside someone like that, with the whole outfit, I always felt like I was a refugee in someone’s back yard. At least the wilderness site moved us away from all that.

Tuesday, July 19, 2011

A Wilderness Site: Part I

I’ve never really liked camping, but Marty was home from the army, and I had grown tired of school after the first week, so, Mom wrote the school a note, and I agreed to go.

Marty had been away for almost three years, stationed for two years in Germany and then for a year in Texas where he met and became involved with this married woman. When that fell through, he jumped on the bus and came home to Indiana for a few weeks. At the time, I didn’t know if he was supposed to be home or if he had just left for a while, but either way, it was good to see him. I was only thirteen when he left, and when he came back I wanted him to know that I was no longer a kid. I had not had my first beer until he had been gone for almost a year, and I wanted Marty to know that now I was like him, that I was someone with whom he could be frank, someone with whom he could be real––that I was a man. And in some ways I was, only it was Marty who would force me to accept adulthood on a level I had not known I was ready for; it was Marty who ultimately knew from way before the moment he stepped out of Aunt Janice’s car, wrapped his hand around mine, and pulled me in toward him, that I was going to have to grow up over the next couple of days, that I was going to be stretched, and that he was going to be the reason. I remember that embrace, and I remember Marty then hugging Mom for a long time––his face buried in her shoulder, his limbs, too long for her small body, reached completely around her back, his hands touching the outsides of her arms. That that impoverished greeting on that cool October eve was significant only became apparent to me afterwards. At the time, I was so eager for Marty to see who I had become that I could not see Marty, I could not realize that maybe there was more to his sudden return than the opportunity for me to demonstrate my manhood, that maybe everything was not all right with him.

I looked rough in those days––the way I thought I was supposed to look. I had long stringy hair that I wore in a ponytail and a black leather biker jacket that Mom had bought me at a pawn shop for my birthday. Usually I wore old jeans and black t-shirts and my jacket. That was my standard look––a style that gave me an identity at a time when I believed that a person’s style defined who he was. Maybe that’s why I never figured Marty was not all right, because, like most people, he had mastered the facade of cool stoicism, a facade behind which lurked a hundred emotions which would never be allowed to surface. He had all his gear packed in a duffel bag, and he was wearing a blue canvas jacket with the sleeves cut off and these beat-up boots that he bought back in Germany. His hair was military length but still somewhat unkempt and wild like he washed it but never combed it. It sort of made him look like a rock singer, a look furthered by his disdainful expression and his pale face. He smoked cigarettes mostly with no hands, the thin cylinder riding between his lips as he exhaled out of the corner of his mouth. Often the ash, perilously long, would simply break off and fall into his lap or down his shirt front. When he noticed, he’d casually brush the ash off his clothing as if the action were a tedious necessity. Marty had begun lifting weights in the military, and besides developing a muscular upper body, the exercise had caused his muscles to tense and the veins on his forearms to pop up and run over them like buried pipes forced up and out of frozen ground. Partly hidden by the sleeve of his t-shirt was a black and red tattoo of a killer whale and the words Moby Dick written in ornate letters. Neither of us had ever read the book, but Marty knew this guy in Germany who was always comparing life situations with scenes from the novel. One night, on a whim, the two got the tattoos, and Marty swore he would read the book to authenticate the art, but as far as I knew, he never did.

Marty had been away for almost three years, stationed for two years in Germany and then for a year in Texas where he met and became involved with this married woman. When that fell through, he jumped on the bus and came home to Indiana for a few weeks. At the time, I didn’t know if he was supposed to be home or if he had just left for a while, but either way, it was good to see him. I was only thirteen when he left, and when he came back I wanted him to know that I was no longer a kid. I had not had my first beer until he had been gone for almost a year, and I wanted Marty to know that now I was like him, that I was someone with whom he could be frank, someone with whom he could be real––that I was a man. And in some ways I was, only it was Marty who would force me to accept adulthood on a level I had not known I was ready for; it was Marty who ultimately knew from way before the moment he stepped out of Aunt Janice’s car, wrapped his hand around mine, and pulled me in toward him, that I was going to have to grow up over the next couple of days, that I was going to be stretched, and that he was going to be the reason. I remember that embrace, and I remember Marty then hugging Mom for a long time––his face buried in her shoulder, his limbs, too long for her small body, reached completely around her back, his hands touching the outsides of her arms. That that impoverished greeting on that cool October eve was significant only became apparent to me afterwards. At the time, I was so eager for Marty to see who I had become that I could not see Marty, I could not realize that maybe there was more to his sudden return than the opportunity for me to demonstrate my manhood, that maybe everything was not all right with him.

I looked rough in those days––the way I thought I was supposed to look. I had long stringy hair that I wore in a ponytail and a black leather biker jacket that Mom had bought me at a pawn shop for my birthday. Usually I wore old jeans and black t-shirts and my jacket. That was my standard look––a style that gave me an identity at a time when I believed that a person’s style defined who he was. Maybe that’s why I never figured Marty was not all right, because, like most people, he had mastered the facade of cool stoicism, a facade behind which lurked a hundred emotions which would never be allowed to surface. He had all his gear packed in a duffel bag, and he was wearing a blue canvas jacket with the sleeves cut off and these beat-up boots that he bought back in Germany. His hair was military length but still somewhat unkempt and wild like he washed it but never combed it. It sort of made him look like a rock singer, a look furthered by his disdainful expression and his pale face. He smoked cigarettes mostly with no hands, the thin cylinder riding between his lips as he exhaled out of the corner of his mouth. Often the ash, perilously long, would simply break off and fall into his lap or down his shirt front. When he noticed, he’d casually brush the ash off his clothing as if the action were a tedious necessity. Marty had begun lifting weights in the military, and besides developing a muscular upper body, the exercise had caused his muscles to tense and the veins on his forearms to pop up and run over them like buried pipes forced up and out of frozen ground. Partly hidden by the sleeve of his t-shirt was a black and red tattoo of a killer whale and the words Moby Dick written in ornate letters. Neither of us had ever read the book, but Marty knew this guy in Germany who was always comparing life situations with scenes from the novel. One night, on a whim, the two got the tattoos, and Marty swore he would read the book to authenticate the art, but as far as I knew, he never did.

Monday, July 18, 2011

Where are we going? Where have we been?

It has yet to be proved that our enormous investment in computer technology in recent years has resulted in increased productivity, or that the ability to “process” hundreds of images and millions of bits of information has anything to do with thinking––with constructing an argument, with making good decisions––much less knowledge in the strong sense.

–Kingwell

So I think of Mark Twain. Even though Ken Burns does not dwell on this fact in his four hour documentary on the guy generally considered the first American writer, Twain spent considerable time wondering whether we, through technology, were personally improving or personally moving further away from perfection. It’s a good question. A fringe group of people out there, some of whom are pretty smart and reasonable, advocate a back-to-nature type of living. Leave the grid. Don’t

burn fossil fuels. Reject electronics. Unify and coexist with Nature. And all this seems well and good. Aren't we at some sort of spiritual peace when we move away from technology, when we get out of town and retreat to the hiking path. Twain liked this idea too, but he also liked inventions and technology. In fact, he lost most of his fortune investing in a type-setting machine. We seem to be comfortable existing in a world of simultaneous yet contradictory messages. I want the newest smart device, a fast internet connection, and HDTV, but I also want a quiet peaceful moment in nature. I want the convenience of the grocery store stocked with prepared foods and canned goods, but I also want fresh produce from the organic local farmer.

To be hip and current, is to drive a hybrid. What a wonderful example of this strange irony. By owning a car, I am willing to tacitly support interstate systems and dwelling miles and miles away from where I work. Yet, by purchasing an energy-efficient car, I am also preserving the environment and shrinking my footprint. What the hybrid really suggests is a commitment to technology; a basic view of I can, through technology, find a way to live the way I want and simultaneously not hurt my environment. Thus, the hybrid owner seems to be on the side of those who believe that we are, by embracing technology, moving toward completion or perfection or self-actualization, not away from it.

Of course my electronic blog could not exist without technology. By using this blog to grapple with the issue of the benefits of technology, I too seem to be saying that I support the idea of technological growth as the path to greater fulfillment. Yet, I hear the nagging voice of good old Thoreau and I wonder. What if I lived in a primitive cabin? Would I achieve greater inner-peace? I mean isn’t inner-peace, contentment, happiness, what it is ultimately about? So either technology increases this, or it decreases it. But now the real issue pops up: fighting against technology is futile.

Even if I were certain that computers were not helping us and in fact were hurting us, society as a whole is so invested in the continuous development of technology, that my voice would be a whisper at best. Most likely, opposing technology, refusing to use email, to text, to even have a cell phone, is simply to become irrelevant and ignored. Only a cranky dinosaur refuses to embrace the newest advancement.

What an interesting word, “advancement.” We do not call new devices technological entrapments. No, they are "advancements." We get excited about the newest app, 3D TV, and touch screen. To reject TV, cell phones, and the web is not only archaic, it’s foolish, especially if I buy into the idea that being connected to the world is a way to increase my happiness.

Montaigne is credited with creating the form now known as the essay. His idea was that writing in this manner is a type of rambling contemplation leading to self-discovery. Today, my blog seems to be following this direction. So what am I discovering? Well, I am thinking about what choices I want to make in my life. I am trying to increase my active participation in the direction my life takes. I am reminding myself that I live in a world that clearly is moving toward and invested in further “advancement.” I am consciously listening to the collective voice of society sending the message that happiness is increased through further development. Yet, I am also reminding myself that this message might be flawed.

Sunday, July 17, 2011

On James Wright

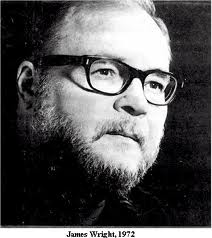

James Wright (December 13, 1927 – March 25, 1980) was a Pulitzer Prize-winning American poet who happens to have been born and raised in Martins Ferry, Ohio. Back then, Matins Ferry was one of the many steel-producing towns along the heavily industrialized Upper Ohio River Valley. The town borders West Virginina. Today, Martins Ferry is a dilapidated forlorn town struggling to survive.

About fifteen years ago I discovered James Wright and have been a fan ever since. Here are two of his best known poems.

Just off the highway to Rochester, Minnesota,

Twilight bounds softly forth on the grass.

And the eyes of those two Indian ponies

Darken with kindness.

They have come gladly out of the willows

To welcome my friend and me.

We step over the barbed wire into the pasture

Where they have been grazing all day, alone.

They ripple tensely, they can hardly contain their happiness

That we have come.

They bow shyly as wet swans. They love each other.

There is no loneliness like theirs.

At home once more,

They begin munching the young tufts of spring in the darkness.

I would like to hold the slenderer one in my arms,

For she has walked over to me

And nuzzled my left hand.

She is black and white,

Her mane falls wild on her forehead,

And the light breeze moves me to caress her long ear

That is delicate as the skin over a girl’s wrist.

Suddenly I realize

That if I stepped out of my body I would break

Into blossom.

A Blessing

Just off the highway to Rochester, Minnesota,

Twilight bounds softly forth on the grass.

And the eyes of those two Indian ponies

Darken with kindness.

They have come gladly out of the willows

To welcome my friend and me.

We step over the barbed wire into the pasture

Where they have been grazing all day, alone.

They ripple tensely, they can hardly contain their happiness

That we have come.

They bow shyly as wet swans. They love each other.

There is no loneliness like theirs.

At home once more,

They begin munching the young tufts of spring in the darkness.

I would like to hold the slenderer one in my arms,

For she has walked over to me

And nuzzled my left hand.

She is black and white,

Her mane falls wild on her forehead,

And the light breeze moves me to caress her long ear

That is delicate as the skin over a girl’s wrist.

Suddenly I realize

That if I stepped out of my body I would break

Into blossom.

Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm

in Pine Island, Minnesota

Over my head, I see the bronze butterfly,

Asleep on the black trunk,

Blowing like a leaf in green shadow.

Down the ravine behind the empty house,

The cowbells follow one another

Into the distances of the afternoon.

To my right,

In a field of sunlight between two pines,

The droppings of last year’s horses

Blaze up into golden stones.

I lean back, as the evening darkens and comes on.

A chicken hawk floats over, looking for home.

I have wasted my life.

So back in 1997 after I had just finished studying Wright’s collected poems, I wrote the following tribute poem. It was actually published, but the publisher wanted me to annotate it so the annotations are included.

In Ohio

Yesterday, I sat alone

Affronting a candled cake,

Knowing that

Extinguishing the flames

Was saying good-bye to you,

James Wright.

One titanic year,

Your collection I lugged

In my bag

In my ghost:

Three pills a day

for a toothless addict. *1

Three tiny teals

under a poplar tree,

Resurrecting anew with the sun.

I broke their necks with my paws

Swallowing nearly all,

Raw and naked. *2

under a poplar tree,

Resurrecting anew with the sun.

I broke their necks with my paws

Swallowing nearly all,

Raw and naked. *2

Neglecting horses

and envying drunks,

I secretly watched little innocent girls

Lick the dew off the Ohio River jungle weed

and cried. *3

The industrial soot

of old Youngstown

Now displays my

tennis shoe print

And I am ashamed.

It doesn’t belong there,

Beside my father’s worn boot.

I did not burn rods

in that filthy shop

forty-seven years.

Still, I am too little

Still, I am too little

for his singed flannel,

To see through the black glass

To see through the black glass

of his hood. *4

James, you have become my horse,

Cantering ankle deep through

The muddy Ohio river towns.

They are too in me.

They are the branch

which will not break. *5

Staring at my disheveled

James, you have become my horse,

Cantering ankle deep through

The muddy Ohio river towns.

They are too in me.

They are the branch

which will not break. *5

Staring at my disheveled

freshmen English class

from the lectern,

from the lectern,

I stand alone.

While deep in the Ohio River

flows old Youngstown,

And my father

And my father

leisurely walks

on her clouded surface

Leading a haltered horse

to Kentucky.

And I know,

I, too,

have wasted my life. *6

*1 I was introduced to James Wright by poet, Terry Hermsen who spent a week working with my students on the writing of poetry. I picked up Wright's Collected Poems and spent the following year reading and studying three a day. Thus the birthday symbolically ends a year with Wright poetry. Toothless addict refers to

Wright's interest in the beat people of the streets. The speaker is alone because Wright loves to use this type of line to begins his poems. He will typically begin with a solitary speaker, move to imagery, and then return to the speaker's response to the imagery.

*2 A teal is a small duck. The word is used by Wright in one of his later poems, "Blue Teal's Mother." Poplar tree is a favorite nature image for Wright. There are three teals a day for I studies three poems a day. Raw and naked refers to Wright himself and his style which is both raw and naked.

*3 Wright loves horses and horse imagery in his poetry. The reference to drunks refers to Wright's alcoholism which he often refers to in his poetry. Watching little girls by the Ohio River is a typical Wright scenario. He likes to set up his poems with isolated speakers sadly

watching and being moved. Wright was from the river town of Martin's Ferry thus the reference to the river.

*4 Here the poem turns personal. Wright wrote much about family. Especially fathers. Thus here is the speaker's home town, the father, the metal-worker, and the speaker's awkward fit into the picture.

*5 As stated Wright is from an Ohio river town and he loved horse imagery. Canter is used by Wright in his poem "Mary Bly" which is about the birth of Robert Bly's daughter. Wright and Bly were great friends. The speaker has also lived near South-Eastern Ohio river towns. The Branch Will Not Break is the title of one of

Wright's poetry collections and the last line in his poem, "Two Hangovers."

*6 Here is the return to the solitary speaker and the speaker's response. Wright and the father are leaving the speaker, Ohio, and are both walking on the river which is the basis of both their lives. The halter is symbolic of

the speaker realizing that by understanding his own father, he will also better understand Wright. The last line is Wright's most famous line. It ends his well-known poem, "Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy's Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota."

Leading a haltered horse

to Kentucky.

And I know,

I, too,

have wasted my life. *6

*1 I was introduced to James Wright by poet, Terry Hermsen who spent a week working with my students on the writing of poetry. I picked up Wright's Collected Poems and spent the following year reading and studying three a day. Thus the birthday symbolically ends a year with Wright poetry. Toothless addict refers to

Wright's interest in the beat people of the streets. The speaker is alone because Wright loves to use this type of line to begins his poems. He will typically begin with a solitary speaker, move to imagery, and then return to the speaker's response to the imagery.

*2 A teal is a small duck. The word is used by Wright in one of his later poems, "Blue Teal's Mother." Poplar tree is a favorite nature image for Wright. There are three teals a day for I studies three poems a day. Raw and naked refers to Wright himself and his style which is both raw and naked.

*3 Wright loves horses and horse imagery in his poetry. The reference to drunks refers to Wright's alcoholism which he often refers to in his poetry. Watching little girls by the Ohio River is a typical Wright scenario. He likes to set up his poems with isolated speakers sadly

watching and being moved. Wright was from the river town of Martin's Ferry thus the reference to the river.

*4 Here the poem turns personal. Wright wrote much about family. Especially fathers. Thus here is the speaker's home town, the father, the metal-worker, and the speaker's awkward fit into the picture.

*5 As stated Wright is from an Ohio river town and he loved horse imagery. Canter is used by Wright in his poem "Mary Bly" which is about the birth of Robert Bly's daughter. Wright and Bly were great friends. The speaker has also lived near South-Eastern Ohio river towns. The Branch Will Not Break is the title of one of

Wright's poetry collections and the last line in his poem, "Two Hangovers."

*6 Here is the return to the solitary speaker and the speaker's response. Wright and the father are leaving the speaker, Ohio, and are both walking on the river which is the basis of both their lives. The halter is symbolic of

the speaker realizing that by understanding his own father, he will also better understand Wright. The last line is Wright's most famous line. It ends his well-known poem, "Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy's Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)